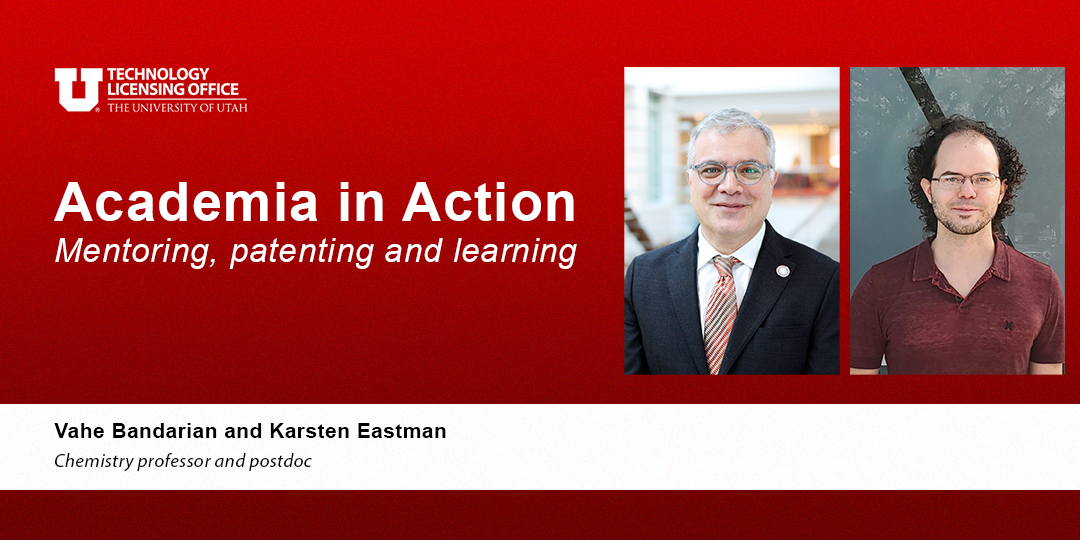

Universities primarily exist to educate students and add to the existing knowledge base. University of Utah chemistry professor Vahe Bandarian and former graduate student Karsten Eastman were able to balance both those goals while pursuing patenting on a new invention that resulted from their research.

Bandarian, a chemistry professor, researches enzymes whose function is unknown but give the cell some sort of advantage. “We basically pick a class of enzymes or a class of molecules and then look at every level from how they're made, what the actual enzyme does, all the way down to the atomic level,” Bandarian said. “We are a lot more focused on discovering new and cool chemistry and enzymes.”

When then-graduate student Karsten Eastman joined Bandarian’s lab, Eastman hopped on one of the available projects, and through some serendipity Eastman and Bandarian realized the enzyme they were studying had the potential to change peptide-based therapeutics.

Typically, enzymes have one job to perform, but this particular enzyme was doing a lot more than normal. “We realized that we might be able to apply this to start making better versions of therapeutics already on the market,” Eastman said. “Once we had this aha moment of, ‘Hey, look, we can actually use this molecular machine to do work on a lot of different things,’ that set everything in motion.”

What they discovered was a way to introduce a better alternative to a disulfide bond. Many peptides and proteins in a human body use these disulfides—or a connection between two sulfur atoms—in their structure, essentially dictating how rigid the structure is. The problem is these disulfides can cause compounds to have a short half-life because the structure is easy to break apart, allowing the body to digest it quickly.

“Now that's great when you're trying to regulate things normally within the body. However, from a therapeutic standpoint, that's a big problem,” Eastman said.

Eastman and Bandarian were able to engineer a process by which an enzyme can install a thioether—sulfur to carbon—bond within a peptide, rather than a disulfide. “It's a much stronger bond. And what that allows us to access is a therapeutic that essentially doesn't have that downside of the short half-life,” Eastman said.

The team has taken multiple existing therapeutics, replaced the disulfide with a thioether and demonstrated that the thioether is more stable in biological conditions while also retaining the activity of the original therapeutic.

“It's a tool that could be applied across pretty much the entire gamut of peptide or peptide like therapeutic agents,” Bandarian said. “I can't tell you that it can be used to make a cancer drug or a weight loss drug but it could be used for all of the above because it is a tool rather than a particular structure.”

Ongoing learning

When Bandarian and Eastman realized the vast potential for their discovery, they realized they had an obligation to the university to not just continue researching the tool, but to disclose it to the Technology Licensing Office and see where it could go.

“At the end of the day, these are the kinds of things that almost every institution wants to do. I think, whether you do something with it or not, you should just disclose it and then let the process take place,” Bandarian said. “It doesn't take a lot of effort to get it in the system.”

Learn more about our new portal for disclosures and more

For the team, the tech transfer process was a worthwhile learning experience that they went through together. After disclosing the tool to TLO, the rest of the process entailed meeting with patent attorneys, discussing the details of their invention, reading and reviewing drafts of the patent, and eventually forming a startup, Sethera, to help them receive more funding and someday have a marketable product.

In the past, Bandarian had filed some provisional patents, but neither him nor Eastman had been involved in something of this scope until they discovered this tool.

As Eastman’s professor and mentor, Bandarian made it clear from the start that his priority was ensuring that Eastman was able to get published, write his dissertation and graduate. “We have a responsibility to disclose, but I also have a responsibility to graduate students,” Bandarian said. “Never lose sight of the fact that you have that responsibility to your students and that trumps everything else.”

Eastman, meanwhile, was able to learn about intellectual property in a hands-on way while continuing to pursue his graduate degree. He successfully defended his thesis in August 2023 and has stayed on in Bandarian’s lab as a postdoc while also leading Sethera as its CEO.

“Karsten was on every call that we have had with the attorneys from the early days. In fact, the way we did all the disclosures is Karsten would come to my office, sit next to me, and we would type the stuff in together and send it in,” Bandarian said. “I involved him at every step of the way, because at the end of the day, he's the one who wants that experience. So, I made sure that he had experience.”